Are You a Boy or a Girl?

Part I: Wounded me

During my childhood, I was a classic tomboy and wallflower.

It wasn’t uncommon for me (a cisgender female) to be mistaken for a boy then. I occasionally heard things like “Hey, sonny-boy” (it was the 70s), “The boy’s section is on the other side, little fella,” and—this is the one that wounded me—“Are you a boy or a girl?”

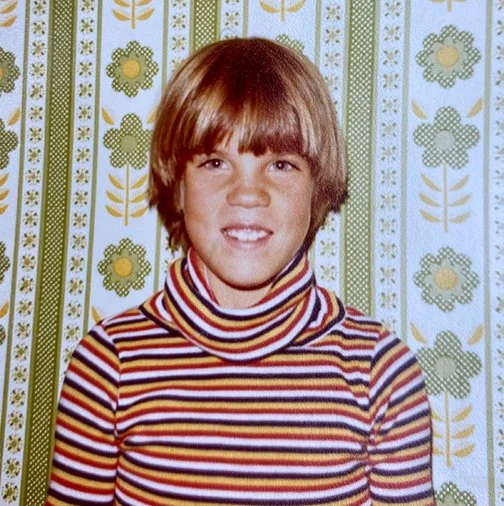

Proudly posing with the new wallpaper my mom and I hung in my bedroom; I was eight years old. (1978)

That last question came at me like a department store announcer on loudspeaker one afternoon at my new school. It was September; I was twelve years old and had just started middle school a few weeks earlier.

The summer before I was about to be unwittingly offered up as fresh, unprocessed meat to jealous and competitive eighth grade girls, I spent a lot of time riding bikes, playing catch, and going to video arcades with Billy and Jason, a couple of guys from my neighborhood. I also spent a lot of time playing with Barbies with my girlfriend Kristen and had a boast-worthy doll collection alongside my baseball mitts and mud-packed cleats. I was really more like a boy-girl than a boy or a girl. I was both things simultaneously; and, spoiler alert, I still am.

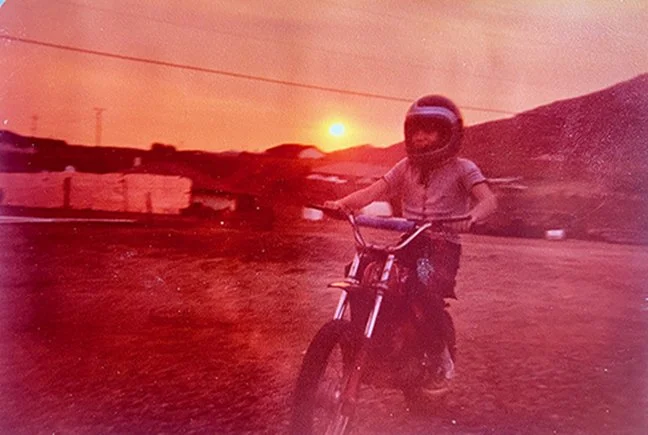

I learned how to ride motorcycles not long after I learned how to ride a bike. I’ve always loved speed and riding makes me feel like I’m flying. (1980)

I was both excited and intimidated by middle school. I liked school, but I was afraid of the rumored drug pushers at every classroom door and the onslaught of new peers and social pressures I would be facing. I was popular and well-liked at my elementary school—a big fish in a little pond. But as outgoing and goofy as I could be around my childhood friends, gymnastics teammates, and family, I was quite shy around people I didn’t know or felt rejected by.

During that same change-filled summer between elementary and middle school, I started having “funny” feelings for the guys I hung out with (hello, nature!), particularly Jason. But it was also the summer that I obsessively asked Kristen if she wanted to tickle each other’s backs when we had sleepovers.

I also liked to play “doctor” with my younger girl cousin whenever they would come over to visit. I was becoming sexually curious, and I think it felt safer and more accessible to express those feelings with girls, even though I was having those same funny feelings for both boys and girls.

That’s me on the right on a deep-sea fishing boat with a family friend. I remember this as one of the most fun days of my life. (1980)

It all felt very natural to me, but my outward ambivalence toward boys and my androgynous appearance presented a problem for my mother. She and I started having strained and uncomfortable conversations around this time about my preference to play sports with boys rather than trying to attract them with my feminine wiles, still lying dormant and heavy at the bottom of my trunk of potentials. I quickly intuited that she feared I was a lesbian.

The truth was that I had been having crushes on boys all throughout elementary school, but I expressed it through competing with them rather than trying to attract them sexually. I foolishly believed that the fastest way to a boy’s heart was to beat him in a race. I wanted respect more than I wanted love, or, rather, respect and love felt like the same thing to me.

Tellingly (foreshadowing the next essay), it was with girls that my feminine side came out. With girls, I wanted to be gentle, intimate, cooperative, and silly. With boys, I wanted camaraderie, competition, debates, and good play on the field.

Playing sports with boys always had a sexual element to it (physical play is an aspect of our libido), and sometimes that inner tension slipped out and the boys would grab my pussy instead of the football.

Getting ready for soccer practice the summer between sixth and seventh grade. I was goalie for my team, The Shinbusters. (1982)

It upset me deeply, but I didn’t want them to know it. I cried and tattled once, but after that, I just competed all the harder with them. I didn’t want to be treated as “just a girl”; I wanted to be treated as their equal, but I was beginning to understand that those two things were mutually exclusive.

By the time I was 12 years old, I already had feelings of shame about being a masculine female who had crushes on both boys and girls and started resenting a world that preferred boys over girls. Even though I felt like a boy-girl at that age, my culture identified me as a girl and made it very clear to me that I needed to adapt myself exclusively to that gender and start putting aside the boy within (more on my “inner Peter Pan” later in this series).

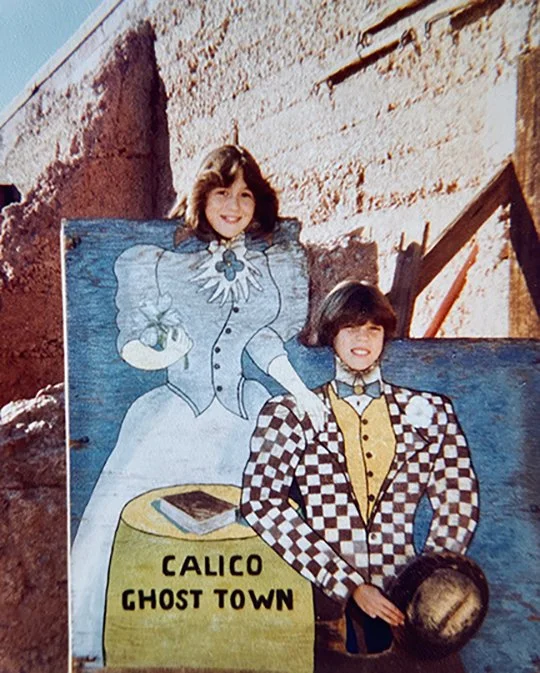

I often played the boy parts in school plays and with my friends, perfectly demonstrated in this photo with my friend, Dawn, who was the Wendy to my Peter Pan.

It was a few weeks into the new school year and it was our homeroom’s turn to get a tour of the school library. Jason, the boy I liked and played catch with over the summer, was already there and sitting at a table with some other kids (both to my horror and excitement, which I apparently couldn’t hide). One of the kids at the table was Carol, an eighth-grade girl who took careful note of the nervous look that Jason and I exchanged.

Having never seen Carol before, I had no idea she also liked Jason. A few minutes later, Carol came over and said to me, smiling, in front of everyone at that table: “I’m sorry to bother you, but we were all just trying to figure out…are you a boy or a girl?”

I was devastated, and a burning shame left me red-faced and speechless. I felt ugly and unacceptable, especially in front of the boy who I liked and who I wanted to like me. It was a humiliating, unprovoked attack, the likes of which I had never experienced before, cementing a deep impression of shame around my appearance.

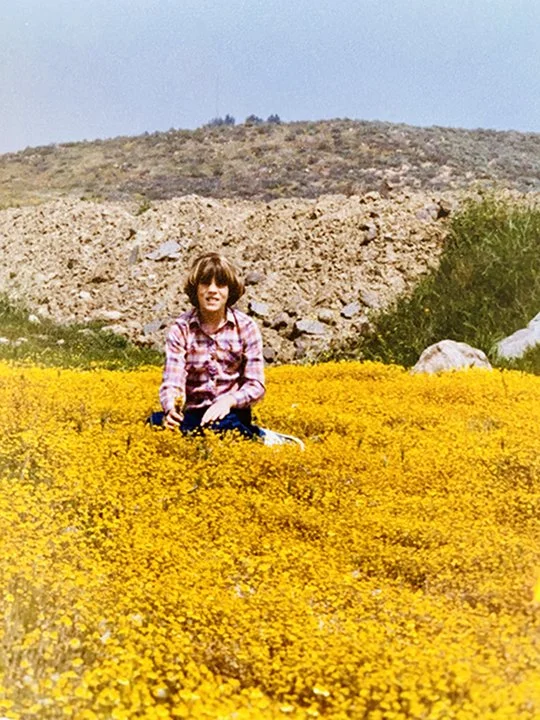

The boy-girl at eleven years old, soon to be swept-up in social expectations of what a girl is supposed to be. (1981)

This was the wound; without my inner masculine side to help me draw boundaries, defend myself, and have the confidence to act and succeed, it was easier to blend in, be invisible, and play the nice, good girl who is pleasing to everyone; a costly sacrifice.

Pouring gasoline on the hotbed of my confusion over my gender, sexuality, and appearance, Carol’s question forced me to answer to my peers and myself. Stunned and dumbfounded, I responded weakly, “I’m a girl.”

***

As petty as a childhood bully may seem to me as a middle-aged adult, this momentary exchange was to have long-lasting effects that became foundational to my self-image and life story. It was such a significant “break in belonging” that it launched me into modeling school the following summer.

As the story continues in the next installment of The Seeker’s Notebook, “Are You a Boy or a Girl? Part II: My magic trick of becoming a pretty girl,” come along for the awkward, uncomfortable, alternately torturous and rapturous experience of learning how to pluck my eyebrows, apply mascara, and sit like a proper lady, and how these new-to-me rules and skills became the scaffolding for the “new and improved” me and the mask I wore as a symbol of this supposedly “better” self.

This essay accompanies the first of my self-portrait series (below), which I am composing to explore the inner dimensions of my personality and the complexes therein. In Self-Portrait #1: Wounded me, I see myself looking back at me from behind a mask; hidden, obscured, and defended. Feeling rejected and abandoned in childhood, I learned to hide behind a mask, which became my superpower and shadow expression.

Self-Portrait #1: Wounded me, 15” x 23 1/2” x 1 1/2”, 2025. Original Artwork and prints available.