My Animus Problem Part I — Good Girl

My Kindergarten photo circa 1975.

As a girl, I was exuberant, confident, and liked who I was. But as I grew, that self-image melted away and I began to believe that I was never enough for anyone or any situation, and my confidence was replaced with insecurity about myself and life in general. The insecurity was deep down, almost unconscious, and the feeling that I was worthless started gradually eroding what natural extroversion and confidence I’d had. Slowly but surely, I became ashamed of who I was, which made me shy and introverted.

By the time I reached high school, I had pretty low self-esteem. I didn’t understand my value then, and I certainly didn’t know how to create self-worth. So, like a flower to the sun, I created my self-image by orienting myself toward the opinions and needs of others, where I perceived all of the value in life to be.

***

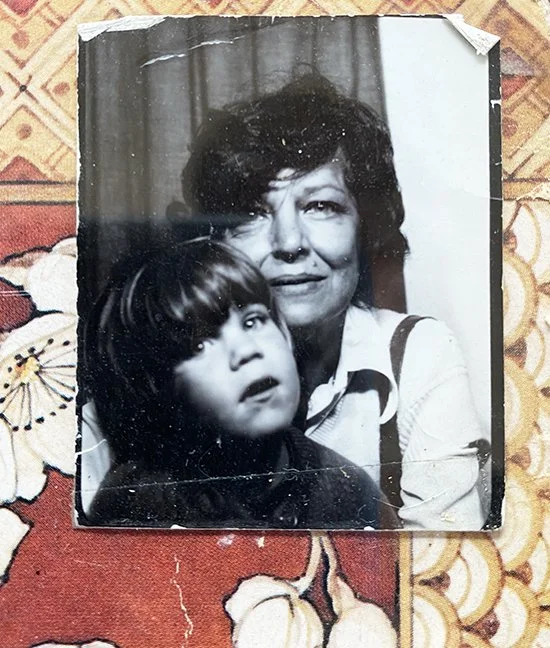

I had a very close relationship with my paternal grandmother during my early childhood. She saw how empathetic and sensitive I was and these were qualities that she also possessed, which was why she recognized them in me. In me she saw herself; a positive projection I drank in like a tall glass of cool, crystalline water. It made me feel like there was something right about me, even though I often felt that something was wrong.

In a photo booth with my paternal grandma, Caroline, circa 1973.

Because we were so close, I naturally held onto something that she and other supportive voices along the way had said to me many times during my formative years: “Christy, you are so good.”

One of my antidotes to my feelings of worthlessness was molding myself into the person I felt others would find valuable and lovable. The approval I received for being “good” made me feel blanketed and embraced, like I belonged and that I had something valuable to offer; it seemed my “goodness" made others happy.

When we’re children we live in a black and white world where things are all or nothing. Following along the lines of healthy childhood development, I felt that I was either good or I was bad, never just a lovable, fallible, ambiguous human. I didn’t feel free to be a whole person; I felt that to gain approval, I needed to conform to an ideal so I would be loved and embraced by others. Even though this is what all humans go through during their indoctrination into society, I unwittingly felt that I needed to try to attain godly status: a perfect being in an imperfect world. It was an impossible task that eventually made me self-conscious, somewhat socially awkward, and a ruthless self-critic. Through the powers of projection, I never felt I was enough for others when in truth, I was not enough for myself or being enough of myself, as it turns out.

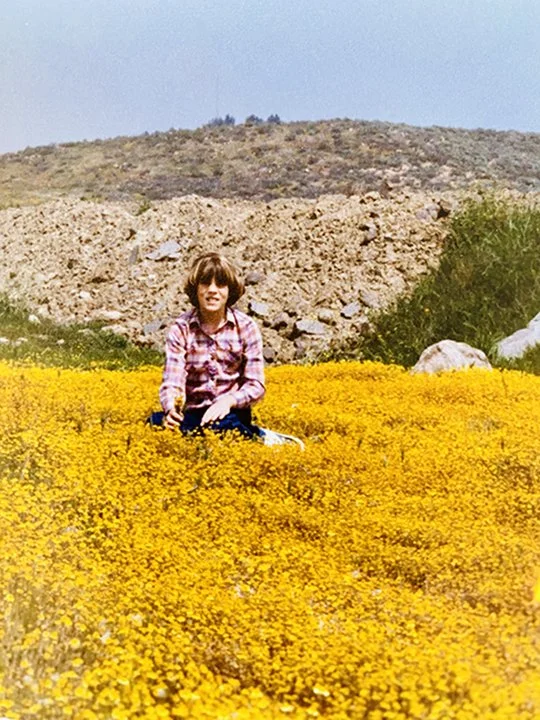

A very awkward 10-year old me, San Bernardino, California, 1980.

Being a good girl became my defense strategy; I felt protected by approval, and being good was my shield, or rather, my mask; what C.G. Jung calls the Persona. When I did not get approval, I felt my totality was being rejected, and a sense of panic and doom would creep over me. I felt that I would be in danger if I didn’t find a way to get the denied approval.

That might sound a little dramatic, but I have always been extremely sensitive to the feelings and attitudes of others. I was born with heightened emotional sensitivity, and it has been both a gift and an affliction; while I can easily empathize and feel your pain, I have to work hard not to take the attitudes, opinions, behaviors, and emotions of others personally. I must continually remind myself that I am not responsible for how others feel or perceive me.

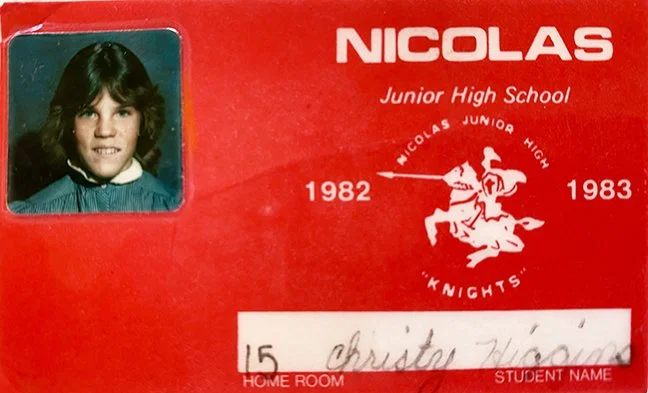

Being “good” wasn’t just a quality I possessed; it became my identity. My goodness was so palpable that I naturally fell into (and excelled at) hall-monitor-type roles in grade school and was sometimes ridiculed as a “goody-goody” at my new junior high school, the shock and sting of which I can still easily recall; like everyone else, I wanted to be seen as cool. In my naiveté, it had never occurred to me that being good could be bad.

7th grade school ID.

However conflicted I felt about being perceived as a goody-goody, being good became my stock in trade. Fortified by approval-drenched dopamine hits every time I felt approved of by others, I went from being a good person to playing the role of Good Girl (which includes other qualities such as “nice” and “pretty,” but let’s just stick with “good” for now; “pretty” came later). The transformation of my “goodness” being something spontaneous and natural to something required and obligatory was seamless. “Being good” went from being one of my many qualities to becoming my pedestal; something on which I could stand above and apart from others.

Because my role as Good Girl required absolute goodness, my bad thoughts and feelings had to be chased from my conscious awareness and hidden in my shadow. I believe that splitting reality into absolute categories of good and bad can eventually lead to a type of split in our minds; we all become fragmented in the process of mental categorization, and I believe it creates, to varying degrees, disorder in our personalities. We don’t need an official diagnosis to know that we’re all a little bit crazy in one way or another. In my case, I developed a type of superiority/inferiority complex, in which in any given situation, I either put myself above or below others depending on which lie I was believing at the moment.

My sense of superiority was fueled by my self-image that I was absolutely good, which made me believe I was better than people who were not; at the same time, my sense of inferiority fueled deeper (unconscious) feelings that truly, I was bad and worthless, and only pretending to be good.

***

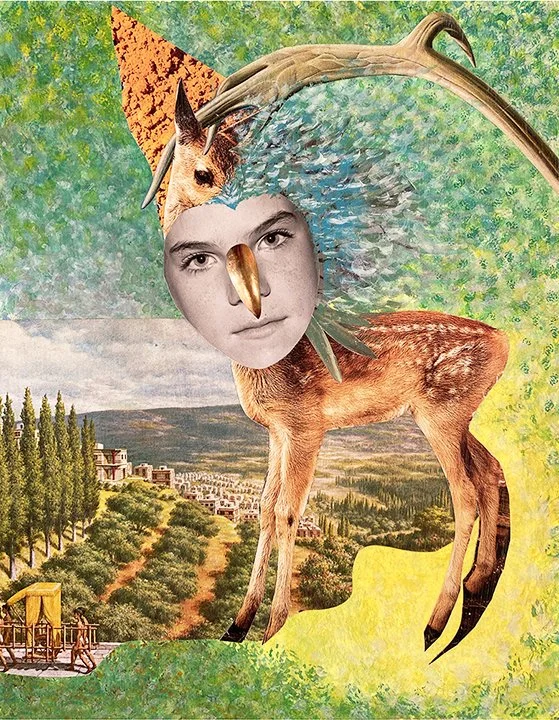

Within our DNA lies all of the possibilities of being human, including both sexes. Whatever is not expressed as a dominant aspect (such as being born physically female) lies in the recesses of our psyche as our interior, inferior aspect. According to C.G. Jung, a man’s outer, conscious maleness is balanced by his inner, unconscious feminine (the anima); whereas a woman’s conscious femaleness is balanced by her inner, unconscious masculine (the animus). When we deny that certain aspects of ourselves exist, we relegate them to our inner domain, overseen by our gender opposite. In other words, the repressed emotions of a female go to her animus, and the repressed emotions of a male go to his anima.

My Animal Nature, by Christy Higgins, 2023, 11” x 14” x 1 1/2”, Mixed-media collage on wood box panel. Original artwork and prints available.

When we aren’t psychologically integrated with both our masculine and feminine natures, and our so-called good and bad aspects, our psyches become polarized, which we see expressed in our beliefs, thoughts, actions, emotions, and behaviors. However, when we embrace the whole spectrum of human experience by accepting ourselves in all of our nature-bound aspects, then we can live in harmony with our inner opposite, and things flow more clearly and congruently in our mind.

In the integrated, rather than polarized psyche, a balance of opposites occurs making one more capable of seeing the relative nature of reality; until that integration occurs, things appear as absolute categories of right and wrong, good and bad, masculine and feminine; the world appears as a realm of opposites.

Since nothing in life is absolute (see Einstein’s Theory of Relativity), things get weirdly twisted up in our minds when we categorize in terms of absolutes. In such a belief system, if I am a Good Girl, then I am absolutely good and there is no room for any bad. If that’s so, what do I do with my bad? This creates a cognitive dissonance in my mind so powerful that I must dissociate—a built-in defense mechanism that splits awareness—to deal with the contradiction between my (painstakingly-crafted) self-image and the naked truth of who I really am. This kind of inner conflict is what laid the groundwork for my future problem with rage, and for a lot of unconscious choices and behavior in relationships with men.

In “My Animus Problem—Part II: Bad Boy”, I’ll be exploring how being a Good Girl led to my lifelong attraction to Bad Boys and how I eventually began to learn that it’s in relationship with others that we begin to see what we’ve been placing in our shadow.

NOTES:

Jung, Carl G. Man And His Symbols. Dell, 1964