My Animus Problem: Part III — The Father Wound

I began writing this essay series as an exploration of my lifelong attraction to bad boys, but soon began to realize that it was going to be about my father, which, in my case, also meant that this series would necessarily need to address abandonment and shame. Huzzah. I should have seen that coming, but I was in denial (i.e. distracted with a busy life). The topic of my father is a dense hotbed of unconscious feelings that my ego does not want to become aware of, so it’s not hard to see why I chose denial.

I’ve long battled a deep feeling of toxic shame that resides at the core of my being, which is and has been a debilitating, confounding emotional condition. When it strikes, it can take me out of commission for hours or days, overpowering me and making even simple tasks seem Sisyphean.

As I naively set out to write about my attraction to bad boys, it’s no wonder that I have felt foggy-headed, contracted, lethargic toward writing, and drawn inward by the gravity of self-doubt and insecurity.

As I lean into the source of toxic shame in my life, the “abandonment wound,” along with all the associated events that resulted from my parents’ divorce, is ignited, temporarily obscuring my ability to perceive anything but fear and self-loathing. In attempting to write about my early life, I have placed a magnifying glass on my past, creating a little fire that has inflamed the old father and mother wounds. Soon, I become the wounds embodied, and the complexes they cause are ablaze within (see the “Stone Witch” series for elucidation). It’s very uncomfortable and further shaming, creating a shame spiral that wraps itself around my rational mind like a hungry boa constrictor. I must wait out the period it takes for the flame of the wound to cool and release the snake that obscures my clarity before I can go back to being my usual friendly, capable, and productive self.

I sometimes wonder if I should be writing about this at all.

Me in Long Beach, CA, 1972.

***

My father, mother, and I lived together in the same house for one year after he returned home from the war in Vietnam; it was early 1971. I was six months old at the time, so I have no memory of him, save one, from that year we lived together as a family.

I am on my dad’s towering, lanky shoulders while he navigates going down a small hill; I stare ahead as the azure-blue Pacific gets closer and bigger. I see green (what I now know to be) Ice Plant on the ground, which quickly give way to the dirty opalescent sand of Long Beach, CA. My mother was walking behind us. We were going to the beach as a family, and all was happy under the bright-windy-blue-sun-filled sky.

Sounds more like a dream, which is how it feels in my mind, and given my age when I think this “memory” is from, it is possibly just a fantasy; I’ll never know. My father wasn’t completely absent from my life, but mostly he wasn’t there. When he was there, he often abused alcohol and drugs and, at times, became violent with my mother, which fractured and traumatized us all (but most of all him, I believe).

***

The psychologist and mythologist Dr. Sharon Blackie says that a father wound impacts a woman’s self-image, self-worth, and confidence. It can show up in a repeated pattern of unhealthy relationships, whereby a woman craves the love and validation she hoped to get from her father. The behavior of our fathers, our primary role model, will form the basis of our expectations of relationships. Dr. Blackie goes on to say that if, as a child, we were abandoned, abused, or criticized by our father, we’re much more likely to tolerate this behavior in adult romantic relationships, whether those relationships are with men or women. That certainly describes some of my experiences in relationships whereby I thought I needed a man to give me a sense of identity and value in the world.

Since we aren’t aware of the images that lie within our unconscious we can often only glean their power and significance in our life through symbols, such as the personalities of other people (which become symbolic in our minds when we concretize, categorize, and judge). With a trick of the mind called projection, our brains begin to perceive the contents of our unconscious personality by noticing and acknowledging that which we hate about others, or, in a mind-boggling twist of irony, that which attracts us irresistibly to certain people.

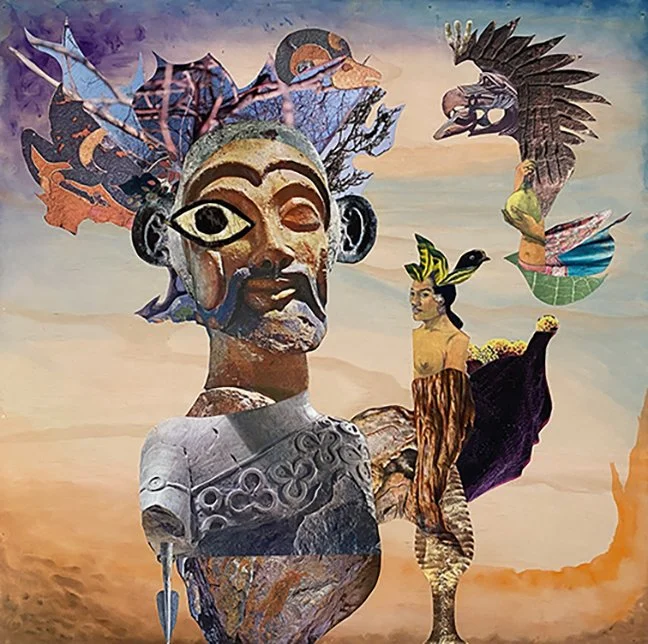

Attraction, 2021. Photograph by Christy Higgins. Prints available.

In simpler terms, any person who can illicit a strong, irresistible, or uncontrollable reaction from us, no matter what sort, has become a canvas onto which we are now projecting an unconscious image, either positive or negative, that was imprinted on our psyche from the past. In this way, we relive our past experiences and traumas over and over again, making life a complicated hall of mirrors for the fragmented psyche. Until we begin to withdraw the projection and learn to see the origins of our fractured perceptions and self-sabotage, we continue to re-create the familiar patterns of our past.

This is all happening subconsciously as we think we’re in control, making “choices”! Something is making a choice in your life, but how do you know if it’s really “you” making a conscious choice and not some unconscious psychological drive that keeps you repeatedly experiencing the same situations? Whether it’s through chronic dissatisfaction no matter what changes you make, or you keep choosing the same type of partner over and over again (or rebounding to their opposite) swearing that you’ll make a better choice the next time, our unconscious instincts, fears, and desires are driving the show. That is, until you give them a name and welcome them to the table.

***

Over the decades, I have often wondered about the mental disturbance and pain that had seemingly locked my father inside of himself, leaving me unattended with my young interpretations and internalizations, ripe for becoming an intergenerational carrier of this unnamed family shadow.

My father in his early 20’s, most likely taken at the communications center where he was stationed in Vietnam. Circa 1971.

When he came home from Vietnam, my father was suffering as a drug-addicted veteran with undiagnosed Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which later included alcoholism. I don’t know all the details of my family history, but I know and have seen enough to understand that unattended pain and shame were living in the spaces between all of us. My father’s father suffered from “shell shock” (now known as PTSD) after serving as a pilot in the Pacific theater of World War II, and upon his return, he, too, self-medicated with alcohol for many years.

Who or what took my father away from me? Or, more integrally, why did my father take himself away from us with drug and alcohol abuse? Was it his emotional wound? Was it my grandfather’s that he inherited? Or was it his father’s father’s? Regardless, it is mine now. I ask these questions to create the necessary suction that I hope will draw up the poisonous sap that lives in this bitter root at the base of my father’s family tree; not so that I can take it in, but so that I can draw it up and spit it out.

A thumbsucker until I was six years old. Circa 1973.

***

It has been difficult to understand my relationships with men from the perspective of my relationship with my father because my relationship with him is and has always been somewhat estranged. Though my parents split up when I was 18 months old, I still visited his side of the family and saw him sporadically throughout my childhood.

When I did see him, things often felt strained between us and I started to avoid intimacy with him; I felt a repulsion toward connecting with him, which in turn, made me feel guilty. What I remember about my father in those years was that he often quietly brooded in his rocking chair in between cigarettes, and rarely smiled, which erroneously made me think he was angry with me. And he always seemed to be gazing outward somewhere beyond the present moment, where I still lived, all the while gazing inward at something I couldn’t see. It was like trying to connect with a ghost, and the idea of being close to him frightened me.

My loving grandmother, to whom I had closely bonded, tried to facilitate my relationship with him, but he and I couldn’t find much of a bond on our own. However, despite the elusive nature of how my absent father helped write my future with men, I’ve begun to connect the dots between my father wound and my lifelong attraction to so-called “bad boys”.

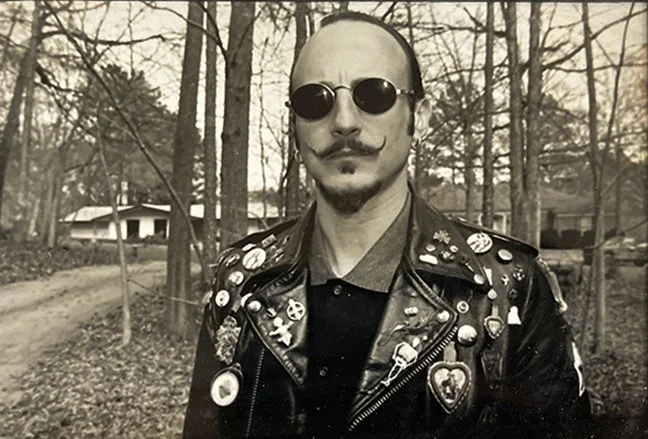

My husband, Dan Piraro, on his Bizarro Among the Savages tour, looking quite the Bad Boy, 1996.

***

The more aloof and “cool” a boy/man was, the more determined I became to be the one to grab his attention. Gaining the attention of a standoffish, disinterested male was equivalent to feeling that the sun shined only on me. Why I wanted to feel special and chosen by an otherwise detached person points directly to my unconscious need to understand why my father chose his addictions over his connection with me.

The feeling of being abandoned by one’s father is tantamount to not being necessary or important to life; I felt that other people (mostly other females) had something that I didn’t possess (namely, a father who “chose” them). To add insult to injury, these deeply painful feelings start growing tendrils of possessiveness, perfectionism, jealousy, and narcissism (placing oneself on a pedestal to feel special, even if it’s a specialness based on your perceived worthlessness or “differentness”). Setting myself apart in this way, I was unwittingly repeating my abandonment trauma over and over again, making connection with others an increasingly difficult challenge for me as I became an adult. This is what being “father-bound” looked like in my day-to-day life.

As children, we are open and pure. We haven’t yet learned how to shut our hearts down or construct boundaries; we’re interacting with the world with our hearts on our sleeves. We want to be seen, heard, known, loved, and to share in the love that we feel through our relationships with our family and tribe. This provides the necessary mirroring that a young person needs to start forming a healthy sense of themselves as separate and distinct from others, an important foundation from which to build a strong ego capable of navigating the world relying on one’s own independent will and creative energies.

During our formative years, when the people around you can’t mirror your feelings back to you, particularly your primary caretakers, the circuit is disrupted and incomplete. When the love you give isn’t received and returned in a positive form, the world starts to feel hostile and dangerous. That’s what it was like for me to interact with my father. In my heart of hearts, as a grown adult, I know that my father loved me unconditionally (and I love him), but when I was a child I rarely felt his love. He couldn’t mirror me because he wasn’t there, or he didn’t seem to be. I saw him, but I couldn’t feel him, and that made me feel alone, even when sitting right next to him. That’s what made him seem like a ghost. Where was my father’s once bright and loving soul that others had told me about?

My father and I, Christmas 1997.

***

I don’t blame my parents for anything (anymore), however, that doesn’t mean that I’m not still taking stock of the way their trauma authored mine. I feel that I’ve been the one left carrying their shadow, and it’s my task to heal these family wounds as they have lived in me and my relationships, particularly those with men. These essays and my artwork are a big part of my healing journey; not being afraid to share the dark aspects of my personality is medicine. Painful realizations such as these need to be faced by each of us if we are to heal this world one precious individual at a time. Questions need to be asked and then patiently contemplated, as the answers sometimes come at a glacial pace. And at other times, strike like lightning in an intuitive gestalt.

I have not relished revealing the personal and family dynamics at the heart of my life traumas. It doesn’t always cast my family in their best light. Nor does it cast me in the golden light of a consistently emotionally balanced person. But it has been my suffering that has led me to consider the suffering of my family, which makes my search for inner peace all the more meaningful. It has helped me understand our collective pain, not just mine, and that the legacy of my family shadow is a testament to the tremendous pain the soul experiences in war and under a patriarchal society that doesn’t allow men to process their emotions, talk about their feelings, and emote publicly. That we deny men the right to their feminine side is a crime against them, just as it is a crime against women to force them to live adhering to a societal structure that keeps them disempowered as second-class citizens. These are the cultural norms that ravish our souls and leave us powerless and addicted in their wake.

In the final essay of this series, I will conclude with how I’ve been integrating my unconscious masculine energies—my “problematic Animus,” in Jungian terms— through adopting attitudes and behaviors of the Bad Boys in my life; and how befriending Bad Girls has been my unconscious attempt to integrate the Bad Girl in my shadow. What at first may have appeared to be imitating others’ personalities, I can now see was a natural way for me to experiment with incorporating my shadow aspects. One could even say that I was perfectly drawn to my husband Dan because he was living my own unexpressed masculine creative energy, and I wanted what he had. I was magnetically drawn to him because I intuited the possibility of my wholeness through him. And boy has he delivered. More on that in “My Animus Problem: Part IV — Bad Girl & Beyond.”

Getting my first and only tattoo, in August 2014. Photograph by Dan Piraro.

***

RESOURCES & FURTHER READING:

”The Father Wound”, The Heroine's Journey 3, Dr. Sharon Blackie, March 27, 2024 (Paid Substack Subscription)

https://sharonblackie.substack.com/p/the-father-wound?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=892383&post_id=142932163&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=false&r=cvp8l&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email

Bradshaw, John. Healing the Shame That Binds You. Health Communications, Inc., 2005.

Jung, Carl G. Man And His Symbols. Dell, 1964.

Woodman, Marion. Leaving My Father’s House: A Journey to Conscious Femininity. Shambhala Publications, 1992.

Woodman, Marion. The Ravaged Bridegroom: Masculinity in Women. Inner City Books,1990.